The first Jewish settlement to be called a ghetto was established in Venice in 1516. This ghetto was extremely different from the places that we now – following the Holocaust – associate with the word ghetto.

In Venice, Jews from the nearby mainland were granted refuge in Venice after fleeing from a besieging army. Prior to this point, an organised Jewish community had not been permitted to exist in the city. After granting refuge to Jews, the leaders of the city ordered that they must live on a single island, known as the Ghetto Nuovo, or the new ghetto. Whilst very different to the Nazi ghettos, the ghetto in Venice was still extremely cramped and overcrowded, and the residents lacked freedom of movement.

Although this is the first recorded incident of a Jewish settlement being called a ghetto, it was not the first Jewish settlement that was confined to a specific area in a town or city by authorities. Jewish settlements, confined to specific areas, had existed for years prior to this point but had been named differently, such as ‘Jewish Quarter’.

Despite this, the word ‘ghetto’ soon caught on, and new settlements termed ‘ghettos’ were established in Ragusa in 1546 and Rome in 1555. These ghettos primarily existed to ensure that Jews and other occupants of the city remained

segregated

. This added to growing antisemitic stereotypes

prevalent

at the time.

New ghettos continued to be established across Italy until the end of the eighteenth century. By the early nineteenth century, the term ghetto had become common across Western Europe. Ghettos for Jews were established in places like Frankfurt and Prague as well.

Following the Enlightenment, ghettos across Europe were legally

abolished

as Jews gained equal rights for the first time, including the freedom to live wherever they pleased. However, despite ghettos no longer existing as physical places in pre-war Europe, the idea of them, who they held, and what they represented, remained. As the Polish Journalist Bernard Singer wrote about pre-war Warsaw ‘There were no drawbridges or guards at its borders; the ghetto had been abolished long before, but nevertheless there still existed an invisible wall which separated the [Jewish] quarter from the rest of the city’ [Bernard Singer, Moje Nalewki, (Warsaw: Czytelnik, 1993), p.7].

The use of the term ghetto soon also spread as a

derogatory

way to refer to other non-Jewish, unenclosed, communities and settlements. One example can be seen in the United States of America where the term ghetto was used to describe spaces where communities of African-American people had settled in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.

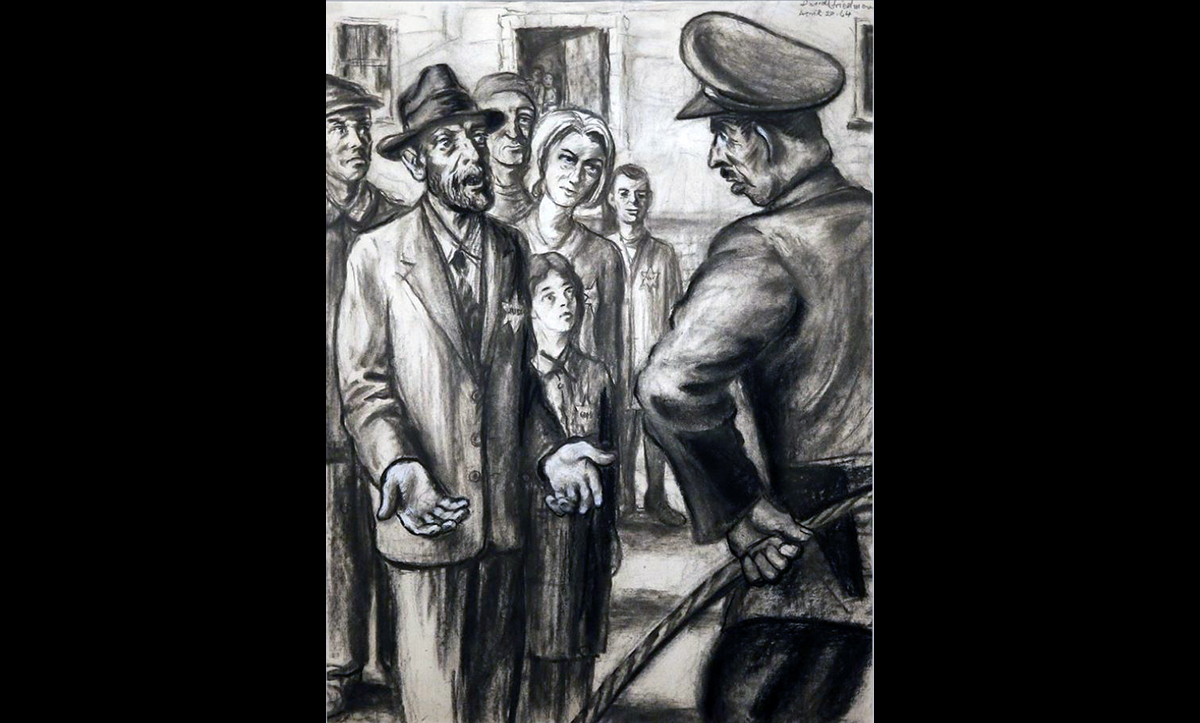

The Nazis’ use of ghettos following the invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939 changed the perception of ghettos forever. The Nazis used ghettos to confine, exploit, and persecute the Jews of Poland and eastern Europe. Thousands of people lost their lives to the inhumane conditions inside the ghettos, and millions more died following the ghettos’ liquidation and the transportation of Jews to extermination camps.